Decorative Cryptography

All encryption is end-to-end, if you’re not picky about the ends.

config TCG_TPM2_HMAC

bool "Use HMAC and encrypted transactions on the TPM bus"

default n

select CRYPTO_ECDH

select CRYPTO_LIB_AESCFB

select CRYPTO_LIB_SHA256

select CRYPTO_LIB_UTILS

help

Setting this causes us to deploy a scheme which uses request

and response HMACs in addition to encryption for

communicating with the TPM to prevent or detect bus snooping

and interposer attacks (see tpm-security.rst). Saying Y

here adds some encryption overhead to all kernel to TPM

transactions.

Last year, I came agross a Linux kernel feature called TCG_TPM2_HMAC. It

claims to detect or prevent active and passive interposer attackers. That’s one

of my sleeper agent activation phrases, so I dug in.

TCG_TPM2_HMAC lives primarily in

drivers/char/tpm/sessions.c

and is discussed at further length in

Documentation/security/tpm/tpm-security.rst.

It all sounds really great. We should care about interposer adversaries. It’s great to use the TPM features that were invented to help us with these problems. Let’s draw a little picture of what’s being attempted here.

In this threat model, there is an adversary who can access the untrusted bus on which all the TPM traffic is sent during the boot. This can be done using hardware hacking or by hijacking another device that controls the TPM bus (e.g., a BMC).

TCG_TPM2_HMAC is a kernel feature, and the kernel boots after the platform

firmware and the boot loader, so it can’t do anything about interposer

adversaries tampering with firmware and boot loader measurements. Let’s assume

for now that the firmware and boot loader are just implicitly trusted to have

booted “correct” code and successfully made honest measurements of all the boot

stages up to and including the kernel. We also implicitly trust the TPM to

behave correctly, here. Or if you have a newer TPM, don’t!

Someone familiar with the STRIDE model can easily observe the following threats just on the big red wire in our picture above:

| Attack | Example |

|---|---|

| Spoofing | Attacker pretends to be the TPM or the CPU to the other device |

| Tampering | Attacker drops or modifies measurements sent to the TPM |

| Repudiation | Not obviously applicable in this case |

| Information Disclosure | Attacker obtains unsealed secrets (e.g., disk encryption keys) |

| Denial of Service | Attacker drops measurements sent to the TPM |

| Escalation of Privilege | Not obviously applicable in this case |

The attacker may or may not necessarily get anything out of manipulating the TPM traffic itself (unless they are some kind of degenerate that just likes to talk to TPMs for fun). But folks who are familiar with TPM-based measured boot and attestation should be able to immediately see the value to the attacker of “modifying measurements” or “obtaining unsealed secrets”.

Let’s take a second to distinguish the two types of attackers here:

- Passive Interposers aka snoopers can only read from the bus but not modify the data.

- Active Interposers can read and write to the bus.

The very best thing a passive interposer can do here is Information

Disclosure: read data from the bus. Since measurements should typically not

be secret, the (legitimate) measurements sent to the TPM are not very

interesting. Unsealed secrets (that were sealed to the measurements in the TPM)

might very much be! That’s why

security/keys/trusted-keys/trusted_tpm2.c

uses an encrypt session

using the helper

tpm_buf_append_hmac_session

which is unfortunately a little bit entangled with the TCG_TPM2_HMAC feature

(but that’s how software development goes). All that really needs to be done

here for this case is to use an encrypt session key established using the EK

as discussed widely by many others but also myself.

The remainder of this blog post discusses the active interposer case.

An active interposer generally wants to do one of two things in this scenario:

- (Tampering, Denial of Service) Tamper with TPM measurements made by the kernel, to falsely attest or unseal as the “intended” code or state, from “unintended” code or state.

- (Spoofing, Information Disclosure) Interpose the TPM connection and defeat the encrypt session solution for unsealing secrets.

The TCG_TPM2_HMAC feature will

establish an auth session

salted (key-encapsulated) to the EK every time the kernel

extends a PCR

or

gets randomness.

You might say to yourself, “self, that’s a lot of overhead (asymmetric crypto

in the TPM) for common, fast operations (PCR extensions, randomness generation)”

and

you’d be right.

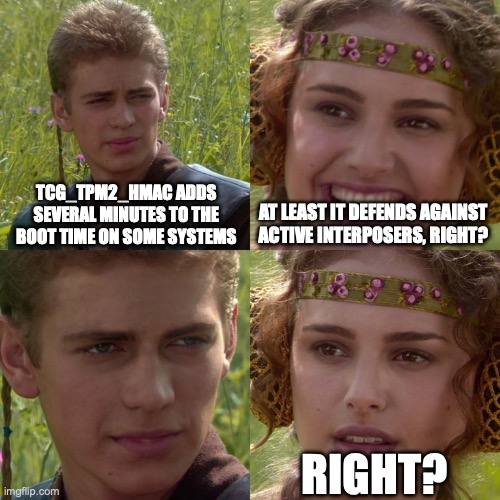

Wow, this feature is expensive! Good thing it’s solving a real problem, right?

Every time a session is needed (e.g., every time the kernel needs to extend a

PCR), the TCG_TPM2_HMAC feature key-encapsulates a new session key with

something called the “Null Primary Key” which is a P256 ECDH key derived from

the Null hierarchy (which means it changes on every boot). It uses this session

key to protect the TPM command by encrypting the inputs and outputs and

adding an HMAC to detect tampering. Great.

One problem: how does the kernel know what the Null Primary Key should be? Read this thread to not find out.

The kernel takes the Null Primary Key at face value and stashes the Name (hash)

of it at /sys/class/tpm/tpm0/null_name and trusts that userspace will

attest the key later using the EK.

This inverts the chain of trust for measured boot: the kernel is responsible for measuring userspace, so that “bad” or “malicious” or “unintended” userspace cannot impersonate “good” or “well-behaved” or “intended” userspace.

This means that all the active-interposer attacker has to do to defeat

TCG_TPM2_HMAC is:

- Replace or hijack the userspace component responsible for checking the Null Primary Key. Call this “Component X”.

- Interpose HMAC session establishment by creating a fake Null Primary Key themselves (e.g., in software) and pretend to be the TPM responding to requests.

- Intercept

TPM2_PCR_Extendcommands, replacing the measurements as desired (e.g., replace “hash of malicious Component X” with “hash of good Component X”). - Malicious component X ignores the “wrong” Null Primary Key name at

/sys/class/tpm/tpm0/null_name.

You can solve this problem by threat model gerrymandering: simply declare that the active interposer adversary is not able to tamper with userspace, which is stored on physical media less than 12 inches away from the TPM in most cases. Note that full disk encryption using the TPM cannot save you here, because if the booting system can fetch the key, so can the physical adversary. If you still think you have a tamper-proof userspace at this point, ask yourself why you need the kernel to measure it anymore.

Adding remote attestation also does not help here, because while a remote system can spot-attest a “Null Primary Key”, it has no way of knowing which key the kernel used when making its measurements.

TPM2_TCG_HMAC was disabled by default again

in August 2025

starting with version 6.18.

What lessons can we learn from all this?

-

Applied cryptography cannot solve a security problem. It can only convert a security problem into a key-management problem.

Corollary: If you aren’t actually solving the key-management problem, your cryptography is strictly decorative. This is not only not helpful, it is actively harmful, because it gives users a false sense of security, leading them to skip other precautions they would have otherwise taken.

-

Chains of trust are directional. Do not invert them.

Corollary:

You know what the chain of trust is? It's the chain I go get and beat you with 'til ya understand who's trustin' who here.

-

Unexplainable security features are just marketing materials.

Corollary: While attestation protocols can be quite byzantine, they should always boil down to 1 or more of “X checks Y against Z” and it should always be possible to explain why X, Y, and Z are each trusted. The explanations may lead to more X, Y, Z tuples, and this is fine, but don’t give up if your questions aren’t being answered.

Corollary 2: When someone comes along with detailed questions about something you’re responsible for, don’t take it personally. Instead, build trust by engaging in a good-faith discussion. You’ll either be right, and your answers appreciated, or you’ll learn about a gap in your system you can improve.

Active physical interposer adversaries are a very real part of legitimate threat models. You need an integrated root-of-trust in your CPU in order to solve these. Check out Caliptra, which provides TCG DICE APIs from within the SoC itself as an integrated root-of-trust. This can be used on its own, or in conjunction with a discrete TPM.

Opinions expressed here are my own and do not represent the official positions of any employer(s) of mine, past or present